A week ago in our “Editorial: Spectacle Chicago and the Death of the JISC,” our readers were provided several key insights regarding juvenile delinquency. First, the connection between early delinquency and the risks of future violence are clear. Second, the closing of the Juvenile Intervention and Support Center (JISC), without any alternative, weakened the city’s response to juvenile delinquency. It remains another spectacle Chicago moment. Yes, large social forces lay a complex macro-level foundation for crime – particularly juvenile crime. But, we should not be fooled, even in areas where crime and violence are the worst, most youth do not become gang members, and most do not engage in violence. Chicago loses children to gang activity, delinquency, and violence one young person at a time. The explosion of carjackings in Chicago provides us with an opportunity for some clarity relative to juvenile crime.

Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

A “Prolific Carjacker” at Age 11

At a press conference on 29 November 2021, the Chicago Police Department (CPD) announced the 26 November arrest of an eleven-year-old boy for carjacking. The youth was armed with a handgun, in a grocery store parking lot, when he ordered the wife of a CPD sergeant out of her car on 14 November. Superintendent David Brown reported that the youth has been arrested before, and he described the 11-year-old as being a “prolific carjacker.”

CPD Chief of Detectives Brendan Deenihan reported that the 11-year-old youth was a suspect in several other carjacking investigations. Chief Deenihan also made clear that this youth was “driving these carjackings” in which he was involved, and he was not just “along for the ride.” The term “driver” meant more than the youth had driven the stolen vehicles. It meant, while he was just eleven, he was an active, even initiating participant in the carjackings. This same youth had been arrested in another carjacking just two weeks earlier. In that case he was charged and released to his parent while that case was still pending in juvenile court.

In September 2018, the Cook County Board sought to entirely ban detentions of youth under age 13 at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center (JTDC). Within five weeks, the cases of two 12-year-old youths raised serious public safety concerns. Juvenile Court Presiding Judge Michael Toomin, noted that the county board had provided no secure alternative to the JDTC for 10 to 12-year-old youth who posed a danger to others. The courts subsequently struck down the county ordinance, as a violation of the judiciary’s authority under the state constitution. Nonetheless, holding a youth under age 13 in custody, pending delinquency proceedings in juvenile court, remains exceptionally rare.

Comments from Chicago’s Mayor:

Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot also commented on this 11-year-old’s arrest at a separate news conference. The mayor’s remarks are particularly noteworthy. Quoting the Mayor: “I’m going to be meeting with the, um, the juvenile judges here, relatively soon, to address that issue. We’ve got a crisis, and it’s a crisis that they’ve got to actually own some responsibility for. We cannot keep putting these kids back out on the streets with no support, no resources, no monitoring.”

The mayor’s comments merit further examination. On this point, here are a couple “cops ask questions“ questions for Mayor Lightfoot:

- Was it not your administration that just days ago closed the JISC, without an alternate plan?

- Does not how the JISC was closed fall within your own criticism of approaches with “no support, no resources, no monitoring?”

- Given the international spectacle of Chicago’s juvenile crime problem, does your administration also “own some responsibility?”

- Given the connection between early delinquency and serious delinquency, and violence, should we not expect more Chicago youth among those murdered in the city?

A Reminder on the Delinquency and Future Victimization

As noted in our editorial on the closing of the JISC, the connection between early delinquency and the risk of both future offending and violent victimization is clear.

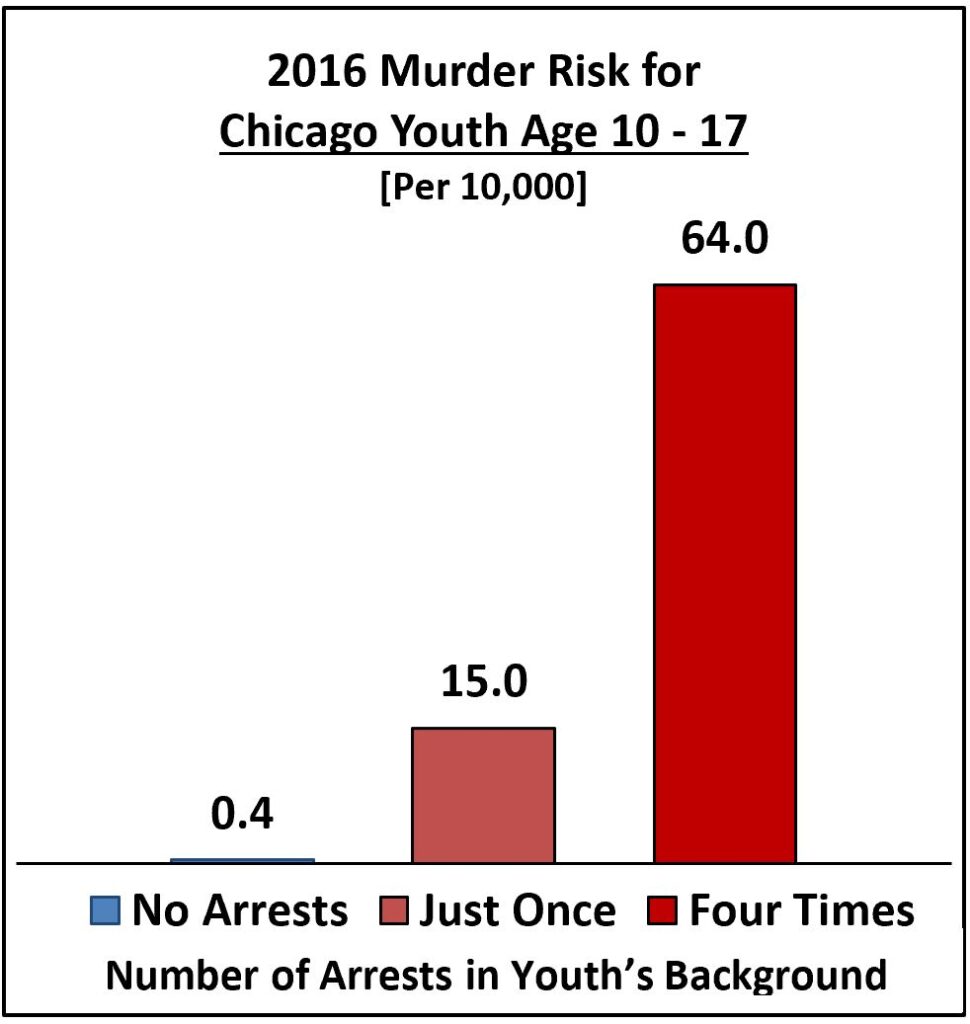

In 2016, the risk of homicide victimization for a Chicago youth age 17 and under, who had never been arrested, was 0.4 in 10,000.

However, with even one arrest, the risk of the young person being a murder victim within one year rose dramatically.

After just one arrest, the murder risk increased to 15.0 in 10,000, which was 38 times higher than the youth who had never been arrested.

With four arrests, the risk was an astonishing 64.0 in 10,000, which was a disturbing 160 times higher than the Chicago youth that had never been arrested.

Scope of the Carjacking Problem

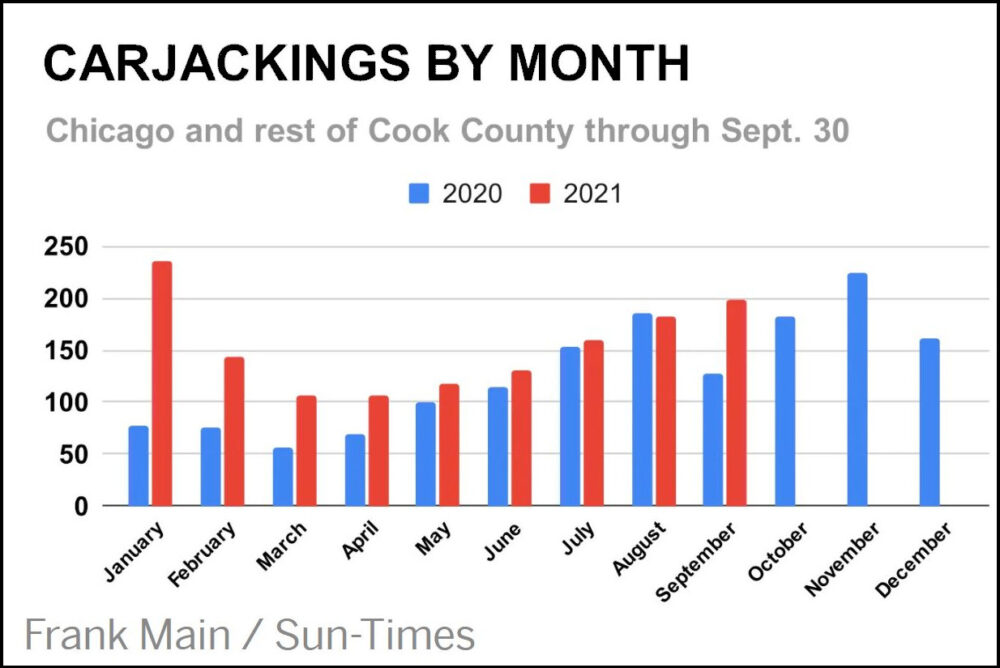

In just the first 21 days of 2021, Chicago had already experienced 144 carjacking incidents. The connections to juvenile crime were already apparent. So too was CPD’s need to increase its resource commitment to address the problem. CPD expanded its detective task force teams, and Superintendent Brown appealed for community resource support to address the juvenile factor. CPD reported that the age range of the city’s typical carjackers was 15 to 20 years old. The youngest carjacker was then reported as age 12. As with the youth from the beginning of this post, since January, Chicago has had other carjacking incidents involving 11-year-old and perhaps 10-year-old juveniles.

Carjacking Charging Challenges:

As of 28 November 2021, CPD reported there have been 1,635 carjacking incidents, so far this year in Chicago, and 1,292 “carjacking-related” arrests. It should also be noted that multiple offenders are often involved in a single incident, and some offenders are arrested multiple times in connection with multiple carjackings. Police, even when they catch carjackers shortly after the vehicle was taken, often have difficulty in getting actual carjacking charges approved by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office (CCSAO). The crimes happen quickly and typically to victims who were caught by surprise. So the offenders driving the carjacked vehicle are often only charged with possessing a stolen vehicle, a lesser Class 4 felony. The additional swarming offenders, if passengers when apprehended, are typically just charged with trespassing to the carjacked vehicle, a misdemeanor.

In October 2021, the Cook County Sheriff’s Office (CCSO) reported carjackings, in the county that Chicago dominates, were on pace to be at the highest levels in two decades.

As of September, countywide there had been more than 1,400 carjackings, with Chicago neighborhoods on the west and south sides the most impacted. As compared to 2019, carjackings in Cook County were up 130%.

As reported by the Chicago Sun-Times: “professional carjackers will work with a ‘chase, vehicle.'” Such further complicates the investigative and charging processes. “After a heist, the ones who grabbed the car will pull into an alley or onto a quiet street so they can trade places with the members of the crew who were in the chase vehicle. That keeps their victims from being able to identify who pulled the gun on them if the stolen car is stopped.” Carjacked vehicles can also be used to conceal the identities of offenders in gang shootings and other street crimes.

An Adult Factor in Juvenile Offender Carjackings:

The more active crews often deliberately include juveniles, to protect the involved adults from serious charges, or to escape detection and charges completely. The CCSO has highlighted the frequent involvement of juvenile offenders in these crimes. In a WGN News interview included in the above video clip, Roe Conn, a former radio personality now with the CCSO, commented: “I’ve had guys tell me that they started doing this as soon as they were tall enough for their feet to reach the pedals. And that’s disturbing on so many levels.”

CBS2 reported that they were “tracking” dozens of cases in juvenile court where adult offenders had carjacked vehicles and were arrested with juvenile co-offenders. On 15 May 2021, John Daniels, a 19-year-old with a prior carjacking history, brought an 11-year boy with him (different than the one mentioned above), as they carjacked a 59-year-old man in the Uptown community of Chicago. The victim of that attack was apparently punched in the face repeatedly by the juvenile offender. The victim fell to the ground with a broken orbital bone. At the initial criminal court hearing for the May 2021 carjacking, Judge Charles Beach denied bail for Daniels. In that decision, the judge noted that Daniels had involved the 11-year-old in the incident.

Daniels had escaped prosecution for a February 2021 armed carjacking when that victim declined to pursue charges. Daniels had been caught by police driving the victim’s carjacked Lexus. When arrested, Daniels had in his possession the victim’s driver’s license, debit card, and medical marijuana card. Unlike many other terrified carjacking victims, the February victim told police he “felt sorry” for the offenders in that incident, and he expressed his thought that “they probably need a car.” That victim’s generosity apparently did not extend to his permanently giving “them” his Lexus, which had been recovered by police.

Fear a Carjacking Victim’s Observations

Fear is a more common reaction among carjacking victims. In 2020, near 92 Street and Kingston Avenue, on Chicago’s southeast side a carjacking occurred. Alyssa Blanchard, a special education teacher, described her experience when she was among Chicago’s 1,413 carjacking victims last year near her home. She described to Ben Bradley, from WGN News, her own fear of being shot. She said she believed she should “not be here,” believing still that she was could have easily been killed. Yet, by contrast, she saw no fear, no remorse, nothing in the eyes of her 13-year-old attacker, who held a gun to her head and demanded that she get our of her car, and leave her purse. Because of her ongoing fear, she planned on moving from her neighborhood.

In the Minds of Juvenile Carjackers

What were they thinking? In November 2021, CBS Evening News conducted interviews with three of Chicago’s youthful carjackers. The answers provided by at least these young people revealed a lack of concern for carjacking victims. Such was likely not a surprise to Alyssa Blanchard, who was very concerned having looked her 13-year-old attacker in his eyes.

“David,” age 14, said: “I like drag them out the car and get in.” He is a fan of video game “Grand Theft Auto,” and wanted to do it in real life – “it looked fun.” “Nicole,” explained being a girl gave her an advantage with victims, who did not expect a girl to carjack them. “Chris” said he committed his first carjacking when he was age 15. He has used cars to just drive through the city. But he has also used carjacked vehicles to participate in gang violence.

Juvenile Carjackers Have Been an Increasing Problem

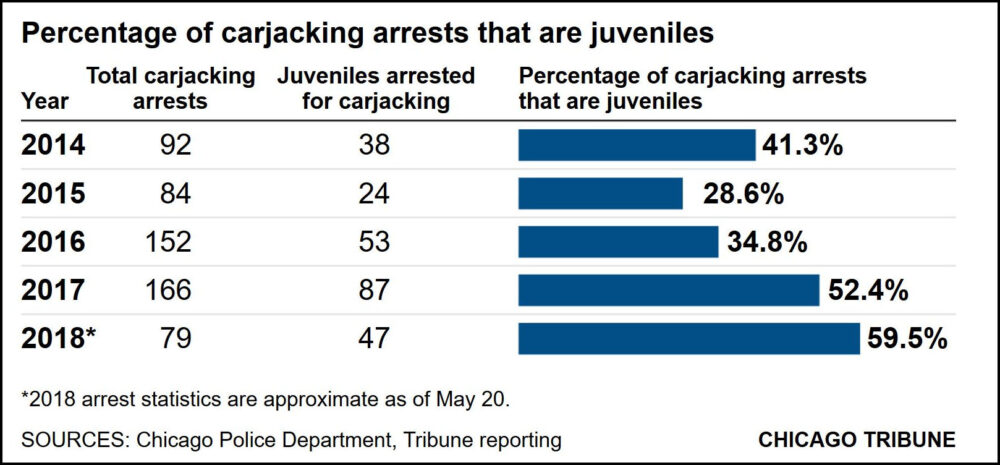

In June 2018, the Chicago Tribune reported on their analysis of arrests for carjacking from 2014 thru 20 May 2018. The Tribune noted both an increase in carjacking arrests and an increase in the juvenile percentage of those arrests beginning in 2016.

In 2018, the Tribune drew a second connection to 2016. Quoting: “As a result of a change in the state law that took effect at the start of 2016, a carjacking charge no longer triggers for those under 18 an automatic transfer to adult court, where the consequences are often far more severe.”

The Tribune analyzed four years of Cook County Juvenile Court and they found “about a third of the minors arrested by Chicago police for carjackings ended up facing less serious charges such as car theft or even lesser offenses.”

The Need for Early Intervention

A CPD Youth Investigations Division analysis of vehicle-theft-related juvenile arrests in Chicago, between 2013 and 2017, identified that two-thirds of these juveniles had been previously arrested at least once for a similar offense. Additionally, of the juvenile offenders arrested in 2017 on vehicular hijacking charges, 39.2% had previously been arrested for Criminal Trespass to Vehicle (CTTV). Clearly, a connection between lower-level delinquency involving stolen vehicles and carjackings was observed.

However, when youth arrested on CTTV charges are referred to juvenile court, a formal delinquency petition is infrequently filed by prosecutors, and the involved youth often do not receive any intervention services.

The CTTV Workshop Effort at the JISC:

The CTTV Workshop Initiative, which began in July 2018, was established by the CPD’s Youth Investigations Division to enhance the response to this juvenile crime issue. Under the initiative, station-adjusted youth arrested for CTTV were required to participate in a three-hour, instruction-based intervention session on a Saturday.

During the workshop sessions, the participating juveniles viewed a video series comprising messages from community volunteers covering the topics of victim impact, the dangers of vehicle crashes, legal consequences from continued delinquency, family, and positive life choices. Additionally, the youth participated in group discussions and completed skills building worksheets focusing on being “in the victim’s shoes,” the physical dangers and potential long-term physical consequences of being in a vehicle crash, the impact on families from continued delinquency and gang activity, strategies for avoiding future delinquency, and establishing positive goals for the future.

With the closing of the JISC, the long-term future of this early intervention effort is uncertain.

BGA Analysis of Juvenile Carjackers:

In July 2021, the Better Government Association (BGA) issued a report, “Few Programs Steer Child Carjackers Away From Trouble.” In that report a key observation was made by the mother of a juvenile carjacking offender. Quoting from the report: “Qiana Matthews, said she badgered court officials for weeks to get her 15-year-old son connected to an intervention program after he was charged with carjacking in October. Even then, her child was allowed to walk away from the voluntary program at a social services agency called UCAN, which provides mentoring and counseling. It was a ‘really good, comprehensive program,’ the mother said, lamenting that her son was simply allowed to opt out after two weeks. ‘He didn’t want it.’”

As was previously noted, the consequences for a juvenile’s early delinquency, particularly when it leads to escalating and chronic delinquency, is an increased risk for violent crime victimization for that same youth. The July report from the BGA, also provided yet another confirming data point for this reality – harsh as it is. The analysis was conducted by the University of Chicago (UC) “Crime Lab,” which has had extended access to multiple Chicago data elements. UC researchers matched the city’s shooting and murder victim data to 1,384 juvenile arrests for vehicle-related crimes from 2018 and 2019. The researchers “found 7%, or 96, were shot or killed within a year.” Ignoring this harsh reality, or worse, concealing the data through expedited arrest records expungement processes, does not change the reality. It does make intervention more difficult and less likely.

More Than Just Offering Involved Youth Services Is Needed:

Allowing youth with these risk factors to “simply opt out” of needed intervention approaches is beyond misguided – its wrong. The “mother’s observation” from Qiana Matthews is consistent with those from veterans of CPD’s Youth Investigation Division who worked with JISC youth. Absent monitoring and follow-up, youth involved in escalating delinquency often simply opt-out. Again, returning to our JISC editorial, services that a youth does not actually attend are no more helpful than are unfilled prescriptions in curing illnesses. Closing the JISC, and reducing the ability for CPD to help foster actual service engagement, remains a significant public policy mistake.

Also a Need for an Adult Factor Sentence Enhancement

Other than within families, babysitting situations, and official youth group mentoring programs, it is unnatural for a 19-year-old and older adults to “hang out” with 11-year-old children. Such associations are classic warning signs for gang activity, criminal recruitment, and child sexual abuse. It is why Secure 1776 founder Thomas Lemmer has for several years advocated for a sentence enhancement statute when adults are convicted of a felony and a juvenile was a co-offender in their crimes.

Under the proposal, Lemmer has proposed for an increased sentencing range similar to those currently in place relative to the use of firearms in the commission of many offenses. Relative to adults who involve juveniles in their crimes, such enhancements should be on a graduated scale. With non-violent felony offenses, an additional year; for violent crimes that did not result in great bodily harm or death to any victim, an additional five years; for violent crimes resulting in great bodily harm to a victim, but not a death, an additional ten years; and for any violent crime resulting in the death of a victim, an additional 20 years.

Adult offenders must be more actively dissuaded from involving juveniles in their crimes. The sentencing proposal seeks greater accountability for such adult offenders. Unfortunately, Illinois, Cook County, and Chicago officials have shown little interest.

We are interested in your thoughts, and invite you to comment below.

Copyright Protected | (c) 2021 Secure1776.us – All rights reserved.

If you are not currently receiving subscriber email notifications, subscribe now.

Juvenile crime is out of control in Illinois. Youths learn quickly that they are not going to be held accountable for their conduct – or misconduct. Once again this is a case of politicians pandering for votes by telling a segment of the population that they can commit criminal acts and wont be held responsible. Without consequences, criminal behavior spreads. Closing the JISC eliminated any chance of social service intervention. Without accountability, this problem will get worse.