On 4 March 2006, the Juvenile Intervention and Support Center (JISC) became Chicago’s first and only police facility dedicated specifically to address juvenile delinquency. In my 34 years, three months, and two days with the Chicago Police Department (CPD), the JISC stands out for two reasons. First, the fact that the doors opened at all was a historic accomplishment. Second, it is a massive disappointment that the JISC stopped receiving youth, as of CPD’s midnight watch on 21 November 2021. In truth, the JISC was never fully supported, not fully implemented, and was not allowed to meet its full potential. And yet, the JISC did good work and offered a pathway for improved outcomes for thousands of Chicago’s young people. Abandoning the JISC, with no functioning alternative, is yet another spectacle Chicago moment.

Estimated reading time: 19 minutes

The Santa Claus Effect

As a young police officer, I observed many arrested youth, including those arrested for the first time. As a group, the youths arrested for the first time, were different than youths who had been arrested before. No matter how much bravado a youth may have displayed to victims or others on the street, most first-time arrested juveniles became very quiet, as they waited in the police station.

You could see them thinking. What would their parents, or grandmother say? What was going to happen now? Nearly all of them had some expectation that they were “in trouble.”

Perhaps when they were younger and misbehaving, their mother may have scolded them. If it was December, mom may have even told them “Santa Claus was watching.”

We have seen that, right? We may even as a child experienced it. A parent warning us. If we were “not good,” then “Santa Claus would not bring us anything for Christmas.” With smaller children, who still believe in Santa Claus, such a warning can cause a “bump up” in compliance, and at least a momentary improvement in behavior.

But what happens once the child no longer believes in Santa? Well, such a warning is not very likely to cause any concern for the child. In fact, the child may even think: “Really? That’s it?” In such cases, getting the child to stop misbehaving probably just became a whole lot more difficult.

As a city, county, and state, we have increasingly told offenders old and young, “there is no Santa Claus.”

Parents and Santa Claus

Now, for many parents, with a child involved in low-level early delinquency, they need only to be made aware of their child’s behavior. They have a plan, the skills, time, and resources to address the issue at home. There is no need for extra help. With those youth, something was going to happen. There would be accountability and parental engagement was all that was needed. No Santa required. Such children know their parents are Santa.

But what if the child and family are in need of help – and none is provided. Well that child is likely to conclude, I did what I did, and so what? “Nothing happened.” There is “no Santa Claus,” and there are no consequences. I can, and will, do as I please. Years of observation, working with youth involved in gangs and delinquency, influenced my thinking, as I helped lead the JISC concept development process. So to were many memories of countless crime scenes and victims – including juvenile victims. When there are no consequences in a courtroom, or in the home, the consequences from a youth’s unchanged problematic behavior can emerge quickly, even violently, on the street.

Early Delinquency and the Risk of Future Violent Offending

In closing down the JISC, Chicago has weakened its response to delinquency. There is now one less resource to help turn children from problematic behavior. As stated above, the consequences from unaddressed delinquency can emerge quickly, even violently, on the street.

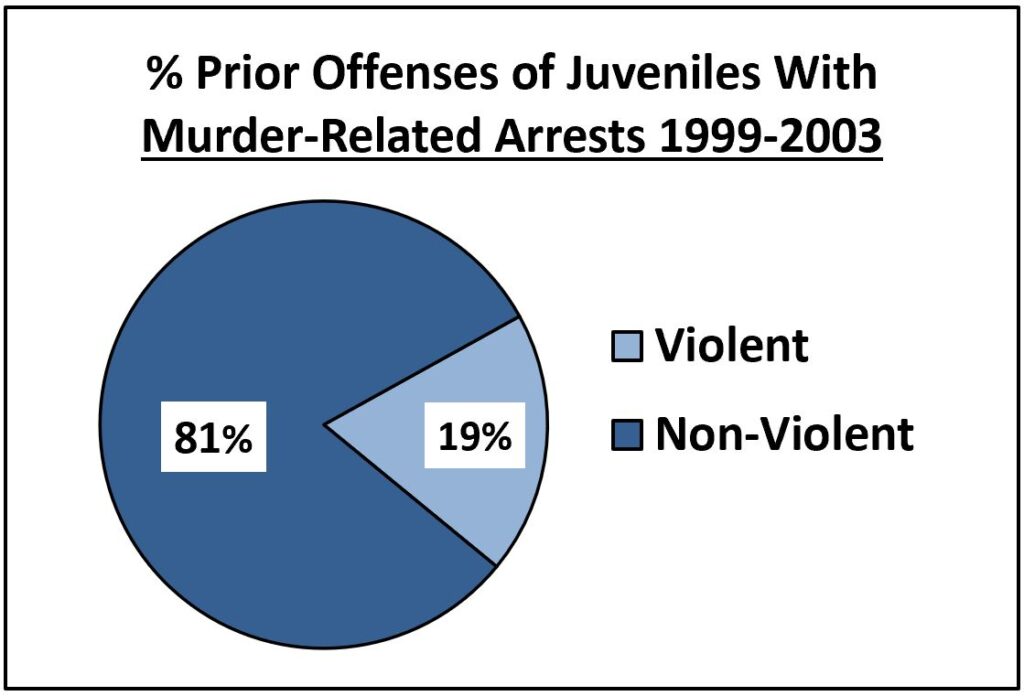

In 2004, I was the acting director of CPD’s Research and Development Division. Our JISC-related analysis efforts included a review of the prior histories of youth subsequently charged with murder or attempted murder. The analysis helped to highlight the connection between early delinquency and subsequent involvement in serious and violent offending.

During the five-year period of 1999 through 2003, 139 juvenile offenders (age 16 or younger) were arrested in Chicago on murder-related charges. All but 12 (or 8.5%) of these juveniles had at least one prior arrest. So our first observation was that a youth arrested on a murder charge was likely involved in some acts of delinquency prior to the murder incident.

Juveniles Arrested on Murder Charges

Combined, the 127 juvenile offenders arrested on murder-related charges from 1999 to 2003 had 516 prior arrests. On average these youth had been arrested four times. As such, on average there were four intervention opportunities with these youth before they were involved in a murder. However, 59 of these juveniles (or 46.5%) had just one or two prior arrests in their backgrounds. For these youth there was just one or two formal intervention opportunities. Therefore, our second observation was, the youth’s formal prior delinquency history may be very limited.

Additionally, the analysis showed that overall the prior arrests were not for violent offenses. In, fact 418 (81.0%) of the combined prior arrests were for non-violent offenses.

Our third observation was, a youth later arrested in connection with a murder is likely to have a history of seemingly minor delinquency.

The three observations from this analysis, taken together, provide a key lesson. A juvenile who is involved in minor delinquency should not be ignored. They may have concluded there is no Santa Claus – no consequences, no need to change course. They may be headed quickly toward serious, even violent offending.

Early Delinquency and the Risk of Future Violent Victimization

In my experience dealing with gang activity generally and juvenile crime specifically, there is a strong correlation between involvement in delinquency and victimization. Youth involved in delinquency interact with others who also engage in delinquent behaviors. Particularly where gang affiliations exist, many of the other delinquent youth are not “friends.” Conflict between these juveniles can involve escalating violence that includes juvenile victims.

A Note on Doing Expungements in a Harmful Way

What anti-system activists refuse to acknowledge is that in real life, there are no “Men in Black” with memory wiping devices to make us forget. Illinois has now joined the growing number of states that automatically expunge most juvenile arrest records – while youth are still youth. They remember they were involved in the fight, street robbery, vehicular hijacking, or shooting. They remember even if any record of their arrest has been expunged.

There is a huge difference between expunging juvenile records after a young person becomes an adult, and doing so while they are still a youth. Expungement is an interesting tactic employed by critics of juvenile court (itself a diversion approach from criminal court), and delinquency intervention efforts like the JISC. Advocates first seek to divert “as many” juvenile arrests away from juvenile court as possible. Then, since the involved youth was not adjudicated delinquent by the court, they seek to immediately erase all record of the arrest.

Here’s the problem. Going back to our 2004 analysis of juveniles arrested in connection with a murder, prior arrests, even minor and diverted ones, are a key warning indicator. Detectives and social workers considering future delinquency intervention options need this information to identify which youth have an escalating risk. A substantially higher risk of being involved in future delinquency as a offender, as well as becoming a victim.

Chicago Juvenile Murder Victimization and Prior Delinquency

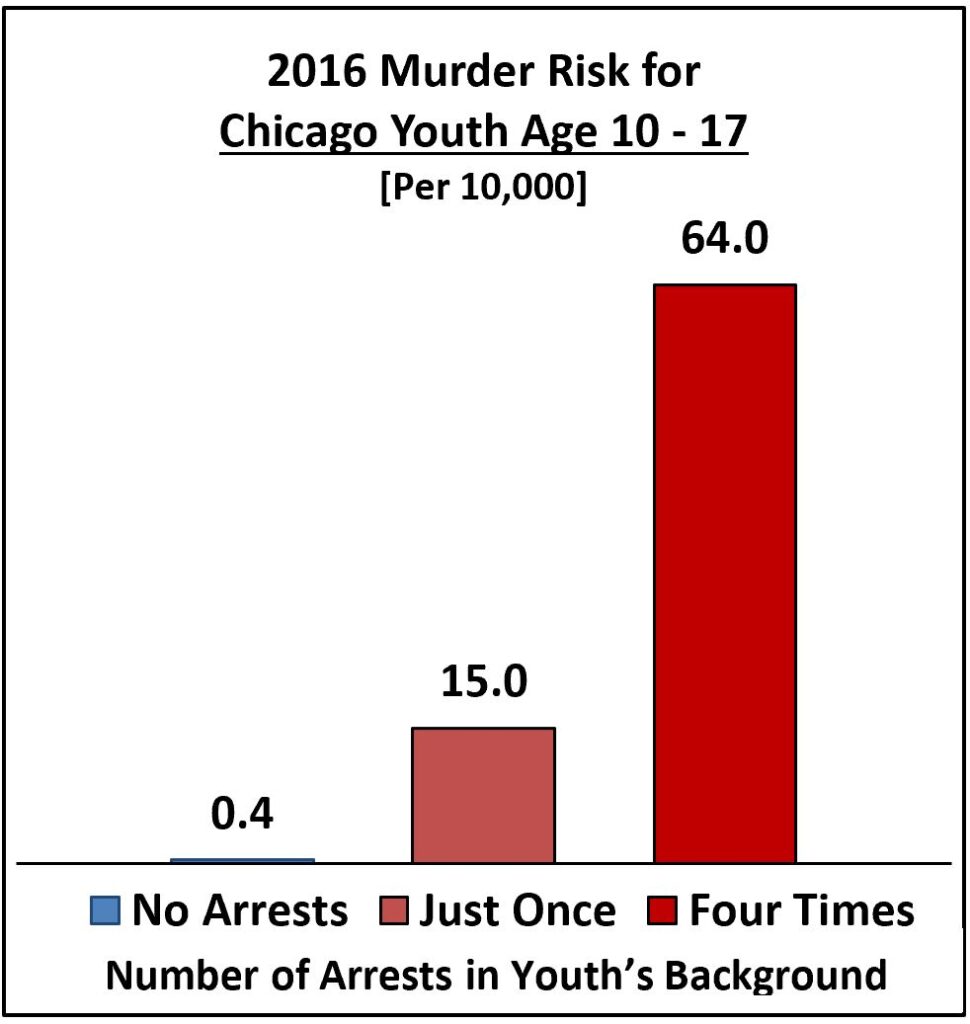

A second analysis of early, low-level delinquency showed the clear escalating risk of future violent crime victimization among juvenile offenders.

In 2016, the risk of homicide victimization for a Chicago youth age 17 and under, who had never been arrested, was 0.4 in 10,000.

However, with even one arrest, the risk of the young person being a murder victim within one year rose dramatically.

After just one arrest, the murder risk increased to 15.0 in 10,000, which was 38 times higher than the youth who had never been arrested.

With four arrests, the risk was an astonishing 64.0 in 10,000, which was a disturbing 160 times higher than the Chicago youth that had never been arrested.

A Need for Urgency

A follow-up analysis of Chicago youth murdered during 2017 examined the prior arrest histories of the youth that were murdered. In looking at the 63 juvenile homicide victims in 2017, nine were age 13 or younger. None of the children age 13 or younger had a prior arrest history, and the victimization dynamics for these infants, toddlers, and younger children were generally different than those involved with the victims in the 14 to 17 age grouping. With the 54 youth murdered during 2017 who were in the 14 to 17 age grouping, the urgency in identifying and addressing early delinquency, as a means of reducing the risk of future violence victimization, was pronounced:

- 75.9% (41) had been previously arrested, and 58.5% (24) had just one to four arrests in their backgrounds when they were murdered.

- 41.5% (17) were murdered within two years of their first arrest, and 26.8% (11) within one year.

- Accentuating the speed at which the delinquency-victimization link can emerge, 17.1% (7) of the murdered youth were killed within six months of their first arrest.

Similar results were observed among the non-fatal 2017 juvenile shooting victims. Of the 380 shooting victims age 17 or younger, 261 (or 68.7%) had a least one prior arrest, and combined these youth had been arrested at least 1,562 times.

It’s Not the Arrest

Of course, a prior arrest is not the cause for the increased risk of being shot or murdered. The increased risk comes from the young person’s underlying activities and involvement in delinquent behaviors. It is their behaviors that places them in risky, even dangerous, situations. Those behaviors may bring them to the attention of the police, and they may be arrested. But tragically – when not arrested – those youth remain in circumstances that have placed them at a substantially greater risk of becoming a victim of serious violence, even murder.

Not Knowing

Due to the implementation of state-mandated annual arrest records expungements, CPD is no longer in a position to do such analysis. Perhaps that was the point. Such information shows the danger that misguided “reform approaches” can bring. We know that Lady Justice is supposed to be blind. Having her suffer from perpetual memory loss serves neither the interests of justice, nor the interests of a young person needing help to resist the pushes and pulls of escalating delinquency. We know “cops ask questions.” The question here is: “who benefits from a delinquency response that provides neither accountability nor effective intervention?”

Before the JISC

In years past, a CPD youth officer or investigator would travel from district station to district station to process the juveniles brought there following an arrest. Consistent with the Illinois Juvenile Court Act, for each arrested juvenile, the youth investigator would be responsible to determine how the youth was to be processed. The seriousness of the incident, the level of evidence, and the youth’s background and arrest history were all key considerations. Two outcomes were most common. First, the involved youth was referred to juvenile court, seeking the filing of a formal delinquency petition and court ordered intervention. Second, the juvenile was simply released to the custody of a parent or guardian, using a court diversion process authorized under the Juvenile Court Act known as a “station adjustment.”

Prior to the JISC, few of these station adjustments included a condition for the involved youth to participate in intervention or support services. Additionally, veteran youth investigators suspected perhaps as few as ten percent of the youth referred to intervention programming actually participated in the identified services. As such, most station-adjustments comprised little more than a warning to the involved juveniles and a notification to their families that they had been involved in problem behaviors that caused them to be arrested.

A Search for Improved Early Intervention

The JISC would ultimately be created through CPD’s efforts under the federal Juvenile Accountability Incentive Block Grant (JAIBG) Program. In 1999, consistent with the federal grant guidelines, CPD formed the Chicago-Cook County Juvenile Crime Enforcement Coalition (JCEC). The initial coalition was chaired by CPD, and it included representatives from the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, Cook County Juvenile Probation Department, Cook County Juvenile Court, Chicago Department of Human Services, Illinois Department of Human Services, Chicago Public Schools, and others including community and civic organizations.

In 2004, the Chicago Department of Human Services (CDHS), was subdivided. The existing agency was tasked with focusing on social issues involving adults. A new agency, the Department of Children and Youth Services (DCYS) was created to focus exclusively on juvenile services. DYCS then replaced CDHS on the JCEC.

It bears noting that the federal JAIBG program authorized by Congress was “designed to promote greater accountability in the juvenile justice system.” This objective was consistent with the stated intent of the Illinois General Assembly, as was recorded in the state’s Juvenile Court Act. Quoting from the act:

“It is the intent of the General Assembly to promote a juvenile justice system capable of dealing with the problem of juvenile delinquency, a system that will protect the community, impose accountability for violations of law and equip juvenile offenders with competencies to live responsibly and productively.” [705 ILCS 405/5-101(1)]

The Need for Accountability

Interestingly, it is the very topic of accountability that critics of the JISC most often resisted, and public safety was never a stated concern. Many city officials, social service providers, and activists failed to fully acknowledge this core principle. Fundamentally, juvenile delinquency intervention efforts must maintain an accountability focus.

A telling statement from one city official still comes to mind: “It is important for the city to have services to offer to youth and their families.”

The urging expressed was more of a political impact statement, and far less an expression of support for accountability. Offering services was popular – even expected. But, ensuring at-risk youth were held accountable to actually engage in those services was not popular with the critics of juvenile court and the JISC.

Yet, youth in crisis are never helped by services they do not actually receive. Too often, court diversion efforts claim success with every referral away from juvenile court. But, if the youth never goes to the diversion services, the referral is little more than a doctor giving a patient a prescription that is never filled.

If a patient receives a prescription, but never fills the prescription and does not take the medicine – how could it possibly provide any benefit?

To be clear, the lack of support for “accountability” in Chicago was not confined to the youth involved in delinquency. The critics of the JISC tended to be singularly focused on dismantling the juvenile justice system. Even as the JISC expanded opportunities for youth to be referred to diversion services, the JISC was still undermined. Further, JISC critics generally were uninterested in examining poor performance among the diversion service providers, or in holding them accountable. The performance of service providers remains a continuing and inadequately addressed problem.

The JISC – An Overview

Following the initial pilot JAIBG approach, CPD reached five key findings. First, directly funding multiple diversion service agencies was problematic. The approach was an administration nightmare. Second, CPD found that it was often funding service providers that could find funding elsewhere. As such, there were missed opportunities to expand the reach of the intervention effort. Third, a case management approach could successfully engage youth in need of services. The station adjustment process could have positive impact when combined with services, compliance monitoring, and follow-up. Fourth, recidivism among juvenile offenders could be reduced. Fifth, contracting for case management services was possible, but difficult. No single private service provider has a citywide program reach. As such, city agency support to the case management process was needed. This has not changed.

In subsequent JAIBG funding cycles, CPD sought to utilize its grant funds to jump start a more permanent delinquency response. Drawing upon the above lessons, CPD began to advance the JISC concept beginning in 2002.

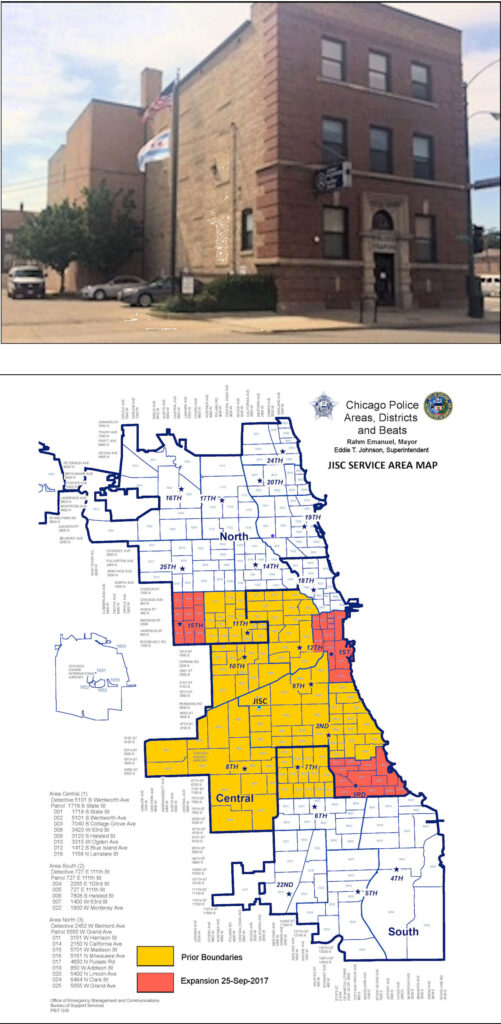

Renovations to create a center commenced in 2004, after considerable maneuvering through a disinterested city bureaucracy. The former district police station and detective area center, built in 1908 and located at Pershing Road and California Avenue, was transformed to serve as the JISC.

The JISC became the location from which the City of Chicago implemented a multi-agency attempt at addressing the complexities of juvenile delinquency. Beginning in 2006, the JISC served five police districts, and by 2017 the center’s service area included 10 districts, including the city’s most violent neighborhoods.

JISC Management

While the JCEC provided input, and some coordination of efforts, the actual JISC operational partnership consisted of (1) CPD, (2) the city’s lead social service agency (either DCYS or DFSS), and (3) a contracted case management provider, which changed multiple times during the life of the JISC. The final case management agency, Lawndale Christian Legal Center (LCLC), was designated by the city in 2021. LCLC is an agency with a limited service area, far smaller than the JISC service boundaries. Additionally, the agency was far more of a legal rights advocacy group than a focused intervention services provider.

As CPD led the effort to open the JISC, I co-authored an article entitled, “Reducing Crime Through Juvenile Delinquency Intervention.” In that 2004 article, I argued: “When examining the potential long-term negative impact on the community, the first-time arrest of a juvenile offender is a big arrest that criminal justice professionals cannot afford to treat as trivial. When treated as an insignificant event by the police, the first arrest represents a missed opportunity at intervention that could lay the foundation for repeated delinquency and perhaps hundreds of criminal acts over a lifetime.”

Meeting this challenge is difficult. The youth most in need of early intervention tend also to be youth that need to be directed more than once. They often come from difficult family circumstances. However, these youth and families were at the very core of the JISC mission.

The JISC Detectives

The CPD detectives at the JISC fulfilled the responsibilities of a “juvenile officer,” under the Juvenile Court Act. All juveniles arrested in the JISC service area were processed by these detectives, with the following exceptions: (a) cases involving the death or great bodily harm to any person; (b) the shooting of a firearm at or by the police; (c) a youth’s possession or use of a firearm; (d) any sex offense; and (e) charges requiring the juvenile to be processed as an adult. Such cases required detailed and immediate investigative follow-up. Arrests falling within those categories were processed at the geographic detective area for the incident. From 2006 through 2020, approximately 76,000 juvenile arrests were processed by JISC detectives.

As with the prior youth investigators, the JISC detectives played a central role in determining whether a youth required court intervention, or could be station-adjusted. Youth arrested: (1) for felony offenses or on juvenile court arrest warrants, or in other circumstances unsuitable for diversion, or (2) with more extensive delinquency histories, or (3) refusing diversion services had their cases sent to juvenile court. Alternately, youth arrested in minor incidents, with no prior delinquency history were released to their parent/guardian without a service referral. But, key to the mission of the JISC, youth eligible for court diversion, but also in need of assistance, were station-adjusted with a service referral.

JISC Detective Diversion Efforts

Consistently over more than 15 years of JISC operations, compared to non-JISC juvenile arrests, minor arrests processed at the JISC were less often referred to court. Additionally, JISC cases were more likely to be referred by detectives to services via the station-adjustment process. Such provided an opportunity for youth, including those who might not receive any intervention referral elsewhere, to get more quickly to services. In 2019, detectives at the JISC station adjusted 18.9% of their cases with a service or program referral. During that same year, area detectives processing juvenile arrests referred just 1.6% to an agency or program.

JISC Case Management

Among the key lessons learned in the initial JAIBG pilot program was the need for immediate outreach to the guardians of the juveniles in need of intervention services. Under the JISC model, whenever a youth was to be station-adjusted with a service referral, the outreach to parents was to be immediate. Upon arrival at the JISC, the detective and case manager would meet with the responsible adult and seek their support for the service referral. This process was known as a “warm hand-off.” Such a direct collaboration between police and social services personnel dramatically improves the likelihood that parents will support the intervention process and the referred youth will actually engage in the needed services. Even when the outreach to parents occurs the next morning, the perception is that “the crisis” has passed. As a result, the involved youth is significantly less likely to engage in the recommended services.

The contracted JISC case management staff coordinated the delivery of services to those youth, age seventeen and younger, who following an arrest had been referred by detectives to diversion programming. From 2006 through 2020, approximately 11,000 youth were referred by detectives to JISC case management for support service coordination.

Coalitions and Political Realities

While a multi-agency effort, in reality only the CPD was at the JISC every hour of its intervention mission. County-level and city-level agencies report to separate elected officials with separate budget priorities and processes. The county agencies never staffed the facility, nor did public schools (not quite a city agency). Such was also the case with the Illinois Department of Human Services and the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. DCYS/DFSS (the two versions of the city’s designated social service agency with JISC responsibilities) did provide the JISC case management function. However, these agencies and their contractors did not operate at the center on a 24-hours-a-day basis.

Secondly, demonizing the police covers a lot of ground. Blaming juvenile court and the police has provided considerable “alternate-response” funding opportunities, as well as a ready-made explanation as to why many youth who were most at risk continued to struggle. Activists have been working for a decade to dramatically alter the formal processes of juvenile delinquency intervention, and they have successfully pressured city, county and state government. They have had an impact. CPD outreach efforts to the families of youth referred to services, but who did not participate, were obstructed. The presiding judge of the Delinquency Division of Cook County’s Juvenile Court was targeted for election defeat, and many judges took note. Then at the state level, the effectiveness of the Juvenile Court Act itself has been legislatively undermined.

A Step Backward

As a beat and gang tactical officer in the late 1980s and early 1990s, I witnessed firsthand a key problem with Chicago’s approach to early delinquency. The first-time arrest of a juvenile for a misdemeanor offense was considered a non-event. Police efforts were completely disconnected from the delinquency prevention efforts of the city’s social service agencies. Additionally, detectives, state’s attorneys, probation officers, and juvenile court judges were focused nearly exclusively on those youth that were already involved in serious, often violent crime, or deeply mired in a pattern of chronic delinquency. For youth not already in crisis, the attempt at intervention to prevent a subsequent arrest typically did not extend past the youth officer asking: “Who can come pick you up.”

Well Chicago, now that you have closed the JISC. Now what? Are police back to just asking: “Who can come pick you up.” Will whatever comes next bring the accountability needed to actually help prevent youth in crisis from engaging in delinquency or falling victim to it?

Or are we just going to wait for Santa?

We are interested in your thoughts, and invite you to comment below.

(c) 2021 Secure1776.us – All rights reserved.

To receive email notifications, subscribe now.

Rarely do I read an article written with insight based on actual experience. Over the course of your career you were the CPD juvenile justice system expert – and this article affirms that. Your points about the value of the JISC are spot on, and supported by data. Closing the JISC at a time when juvenile crime is off the charts, is ridiculous. By not having any social service alternative in place, the city has essentially abandoned the most at-risk juveniles.

It does seem that for the anti-police and anti-juvenile-court critics, their “cause” trumps all else. Going back to the very first pilot JAIBG efforts, it is clear that the patch work of private social service provides is not an adequate response. No single agency in Chicago has anything close to the geographic reach that the JISC had. And couple that with the 24/7 presence of CPD at the JISC, the scale opportunities the JISC provided were even more evident. For many, the idea that the police could be a more reliable gateway to services than any other single Chicago agency was, and is, a narrative they will not accept. It is inconsistent with the “cause.” Actually helping youth is secondary to the mantra of the narrative.

The closing of the JISC makes you wonder what are the mindsets of the political and operational leaderships responsible for this action.

The proliferation of juvenile initiated offenses ,particularly carjackings in the Beverly and Calumet Heights neighborhoods and the removal of Chicago Police school resource officers would theoretically result in an expansion of JISC services .

There needs to be an accounting and analysis of the political and administrative dynamics that precipitated this action.

Even a scaled down operation with a laser focus on juvenile crime issues is better than a tepid nonexistent or diffused response.

Indeed. The mindset and political motivations resisting the JISC and culminating in its closing are troubling.

As noted above: “The JISC was never fully supported, not fully implemented, and was not allowed to meet its full potential.”

The JISC concept provided a workable prototype and a foundation from which to build an improving and coordinated all-levels response to juvenile crime. Well, if that is what was truly desired. It seems that for some, an all-levels response was not desired. Such does not fit their political narrative.

The truth about consequences (a continuing focus for Secure 1776) is that when consequences are not played out in courthouses, formal diversion programs, and the homes of Chicago’s youth – they play out in the streets.

We can be sure of this: the medical examiner’s office in Chicago won’t be closing anytime soon.

Great article! One thing I would like to add is LCLC was contracted for the JISC in November of 2020 to the tune of 900k dollars. Initially providing services for only 3 JISC districts when the JISC covered 10 districts. Children in the other districts were without service plans for months!

They later claimed to be providing services for all 10 districts. From where I stood, I saw mainly referrals compared to case management plans! I think an audit on the services provided should be done! No doubt we will find that the city’s plan had nothing to do with youth but again was nepotism at its best! Now that the JISC is closed where did the rest of that 900k go? Youth are once again being processed in the Areas. CPD has moved backward instead of forward! This should not be acceptable!

Thank you for your efforts at the JISC, and your observations above.